K Kruger

TVWBB 1-Star Olympian

This is an extended answer to this post.

Though I quite agree with David, Mike and Steve M, if you'll allow some further commentary...:

A few points: In the case of pork, a temp of 137 internal (and held for a bit over 2 minutes, in all parts of the roast) needs to be achieved to kill trichina. Trichina is extremely rare in mass produced pork but, nevertheless, trich can be eliminated by a combination of temp and time at temps lower than 144, right at 144 for instant kill. (See here.)

Pasteurization--the reduction of food-borne pathogenic bacteria to levels considered safe--is a product of time @ temp. Single-number kill-temps like one sees--e.g., 165 for poultry, 155 for burgers, 'boiling' (212) for cryptosporidium in water--while not inaccurate per se, belie reality.

Pasteurization begins to occur when the temp of the raw food item moves past the top end of the 'danger zone'. This top end is slightly higher than 127 so, for all practical purposes, we can call it 130 (not 140 as is commonly assumed). At that point pasteurization becomes a time @ temp issue, in other words, how many seconds or minutes at a specified temp is the food item held--yet in other words, if a given food item is cooked to X temp and held at that temp for Y number of minutes/seconds, the food can be considered pasteurized and safe. There are equivalents as well, in other words, if the same food item is cooked to Xx temp and held at that temp for Yy minutes/seconds then precisely the same pasteurization level is achieved. I'll get back to this below.

Pasteurization, again, is the reduction of pathogenic bacteria to safe levels. It is not sterilization; sterilization is the destruction of all ('all' being relative) bacteria, which commercial canning pretty much does--something not desired for most cooked foods because it also destroys flavors (if you've ever had sterilized milk you know exactly what I'm talking about). Because there is no 'zero' in microbiology (i.e., some pathogens will always survive), pasteurization is referred to a 'log reduction', meaning the level of reduction expected per gram of food such that it becomes safe to eat.

Reduction of Salmonella to safe levels is used by the USDA to set the pasteurization standard and the FDA has copied this standard as well. Reducing the bacterial load is called a 'log reduction', as noted, and is abbreviated by a number plus the letter D which stands for decimal. The standard starts at 5D--spelled out, a reduction by 5 decimal (5D) reductions, or 100,000 to 1 per gram of food (10^5 to 10^0). Since there are probably no more than 100 Salmonella per gram to start, this reduces the Salmonella to 1 organism per 1,000 grams of food. Greater Ds are used in other circumstances where standards are for log reduction are higher. 6.5D is standard for most intact roasts, 7D for poultry items, 12D for canned items.

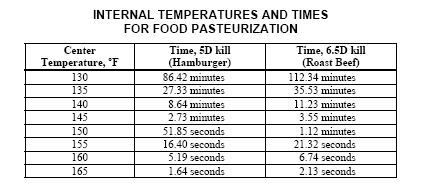

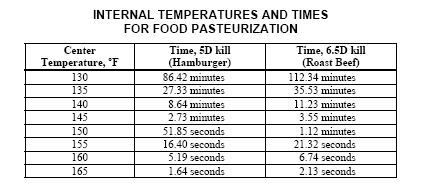

Take a look at the chart below.

Each time/temp relationship is equivalent. In other words, the same level of pasteurization occurs on a food items cooked to 130 and held there for 112 minutes, or cooked to 150 and held there for 1.12 minutes, or cooked to 165 and held there for 2.13 seconds. While this isn't practical for a cooking on a grill, say, it might be if one is cooking in an oven where specific lower temps can be maintained. This is often done in restaurants that cook sous-vide or that cook using combi ovens, ovens that are designed for specific cook-and-hold situations. But one could, e.g., if one wanted a rarer burger, grill one to 140 internal then hold it in an oven that could maintain the requisite 140 for 8.6 minutes to get a 5D kill. (The temperatures and times listed in the table are also sufficient to also destroy E. coli O157:H7 in food (e.g., ground beef).) Regardless, the chart points out the dynamics of time @ temp.

For poultry (a 7D standard) the operative times are thus:

Temp Reached/Minimum Time for Chicken/Min Time for Turkey

140/ 35 Min / 33.7 Min

145/ 13 Min / 13.8 Min

150/ 4.2 Min/ 4.9 Min

155/ 54.4 Secs/ 1.3 Min

160/ 16.9 Secs/ 26.9 Secs

165/ <10 Secs/ <10 Secs

As you can see, for all practical purposes cooking to over 160 internal is not required for pasteurization. It can be required--especially in the case of poultry but also, for our purposes, in the case of barbecue, to cook to higher internals for quality purposes. Turkey thigh, e.g., isn't very palatable, imo, at 160, and brisket is barely chewable; both, however, would be safe to eat if they reached 160--that is if one could.

It should be clear that having an accurate thermometer is of utmost importance. Interior juices can be of any color and so can interior portions of the product being cooked. Young chickens frequently maintain red/pink color near the bones after cooking to safe internals; hamburgers might be grey thoughout even when raw or might maintain bright red coloring internally even after safe internals are reached, especially if other products were added to the meat before the burger was formed. Temperature is the only operative issue--not color.

Tip-sensitive thermistor or thermocouple thermometers are the best for checking internal temps (make sure they're accurate!). Non-electric, dial stem terms should NEVER be used for thinner items (imo, they shouldn't be used for checking internals of anything) as they can be wildly inaccurate. This is because they have a 1- to 2-inch-long bimetallic spring in the stem. The thermometer must be immersed in the food more than 3 inches, and the temperature reading is still only the average temperature across the bimetallic coil, or about 3 inches up the stem from the tip. This temperature measuring device is suitable for measuring the temperature of liquid products such as soup, where the temperature throughout the product varies only 1 degree, and items that are more than 3 inches thick--but to assure accuracy a tip-sensitive therm is best. Again, bimetal therms should NEVER be used for thin items like burgers and chicken breasts.

This is already a long post but I wanted to make another point I've made many times elsewhere, and one that is important to this thread as it is clear that the beans were being cooked one day for consumption the next, as many of us do as a matter of course when we cook ahead of time or cook more than we are going to consume immediately. The important point is the need for relatively rapid cooling after cooking for food items meant for storage for reheating/consuming in the future.

As discussed, pasteurization that occurs during cooking reduces the possible pathogens to a safe-to-consume level. Once the cooked item's temp falls to less than the top end of the danger zone (again, 130, and I am talking about any part of the product which, practically speaking, is usually the surface temp and not the interior as surfaces cool more quickly in most cases) then growth of any existing pathogens can occur (pathogens that might have survived pasteurization). The critical temp range--the range in which relatively rapid growth by the largest amount of different pathogens can be expected--is 85-115.

Once a food item's temp has moved into the danger zone the clock starts, growth occurs, and food must be consumed in a reasonable period of time so as not to pose a danger. This 'reasonable' time is what constitutes the '4-hour rule', meaning that food should be consumed within 4 hours of its temp moving to less than 130 (or above 40 in the case of cold foods that are warming up). The actual time is dependent on the temps and the time so, like above, it is really a time @ temp situation. Without going into further details on this at the moment, suffice to say that if food is not going to be consumed in less than 4 hours any part of the food items falls to less than 130 (or rises, in the case of cold foods, to more than 40), it should be cooled quickly then fridged or frozen.

Items like pork butt and brisket that are often rested for a prolonged period can be temped by placing a therm on or near the surface of the item before foiling and placing in a cooler for resting. After the rest, and provided the temp has not dropped to less than 130, the butt, say, can be removed from the foil and pulled while still hot. But the pulled pork should then be cooled quickly (NOT packed in bulk while still warm/hot as cooling will then take too long) by placing it shallowly in roasting pans, cooling further, then placing in the fridge to finish cooling before packing and storing. Alternatively, pull the pork, allow to cool by placing the pork in shallowly in a pan during pulling, then place smaller amounts in larger Zip-locs or FoodSaver bags. These bags can be sealed then place flat in the fridge or freeze (preferably with airspace under them) to finish cooling. The thickness of the pork should not be greater than 1 inch.

This appoach can work for soups, pots of beans or chili, and sauces as well. Alternatively, the entire pot of the item can be place in a sink of iced water (taking care that the water/ice level is lower than the rim of the pot, of course), and the pot stirred from time to time so that its contents cools evenly, and draining some water and replacing it with more ice, as needed.

Again, hot food items are in the danger zone when their temps drop below 130; cold items when their temps rise above 40. If the temps are maintained outside of the danger zone there are no safety issues and the food items can be held at correct temps for very long periods (though excessive periods often cause quality problems, there aren't safety issues). Safety concerns begin with the temps fall or rise into the danger zone and the concerns grow as time in the zone grows.

Though one sees food-borne illness (FBI) that occurs from undercooked foods (burgers, e.g.) or contaminated raw foods (the recent E. coli in spinach issue), by far one sees a greater occurrence of FBIs from foods that have been 'temperature abused' viz. foods that have been allowed to enter and remain in the danger zone for too long. This occurs most often during holidays (because of food cooked in advance and improperly cooled before being reheated, or from leftovers) and during the summer months when picnics/outdoor eating are commonplace (for the same reasons). If food is placed out on the holiday or picnic table without temp control (chafers for hot items, iced platters/bowls or some other method of maintaining cold) for cold items, the food should be consumed relatively quickly--in less than 4 hours, in most cases. Food not consumed in this period of time should be discarded--not saved. Though the length of time the food will remain safe varies according to time @ temp guidelines (some items might be safe for many more hours than 4, depending on the item, the specific temp that the item reached and the range of temps in the danger zone that occurred (was it a cold item that had an increase from 40 to 65 over 4 hours? a hot item that fell from 130 to 105 over 3 hours?), unless you know this information, temped the food while it sat on the table, watched the clock, etc., for practical purposes it is best to assume 4 hours maximum--and then pitch all food after that point. Storage and then consumption of food that has been in the danger zone for more than 4 hours is not recommended. Technically, again, depending on the variables noted above, the food might be safe for storage and later consumption, (I am not automatically assuming of FBIs from these foods would occur), at the very least I would not serve foods that have been in the danger zone for loonger than 4 hours, then stored, to children, the elderly, or those with compromised immune systems as these individuals are far more succeptible to FBIs.

Kevin

On edit: Edited trichina time/temp info and provided explanatory link

Though I quite agree with David, Mike and Steve M, if you'll allow some further commentary...:

A few points: In the case of pork, a temp of 137 internal (and held for a bit over 2 minutes, in all parts of the roast) needs to be achieved to kill trichina. Trichina is extremely rare in mass produced pork but, nevertheless, trich can be eliminated by a combination of temp and time at temps lower than 144, right at 144 for instant kill. (See here.)

Pasteurization--the reduction of food-borne pathogenic bacteria to levels considered safe--is a product of time @ temp. Single-number kill-temps like one sees--e.g., 165 for poultry, 155 for burgers, 'boiling' (212) for cryptosporidium in water--while not inaccurate per se, belie reality.

Pasteurization begins to occur when the temp of the raw food item moves past the top end of the 'danger zone'. This top end is slightly higher than 127 so, for all practical purposes, we can call it 130 (not 140 as is commonly assumed). At that point pasteurization becomes a time @ temp issue, in other words, how many seconds or minutes at a specified temp is the food item held--yet in other words, if a given food item is cooked to X temp and held at that temp for Y number of minutes/seconds, the food can be considered pasteurized and safe. There are equivalents as well, in other words, if the same food item is cooked to Xx temp and held at that temp for Yy minutes/seconds then precisely the same pasteurization level is achieved. I'll get back to this below.

Pasteurization, again, is the reduction of pathogenic bacteria to safe levels. It is not sterilization; sterilization is the destruction of all ('all' being relative) bacteria, which commercial canning pretty much does--something not desired for most cooked foods because it also destroys flavors (if you've ever had sterilized milk you know exactly what I'm talking about). Because there is no 'zero' in microbiology (i.e., some pathogens will always survive), pasteurization is referred to a 'log reduction', meaning the level of reduction expected per gram of food such that it becomes safe to eat.

Reduction of Salmonella to safe levels is used by the USDA to set the pasteurization standard and the FDA has copied this standard as well. Reducing the bacterial load is called a 'log reduction', as noted, and is abbreviated by a number plus the letter D which stands for decimal. The standard starts at 5D--spelled out, a reduction by 5 decimal (5D) reductions, or 100,000 to 1 per gram of food (10^5 to 10^0). Since there are probably no more than 100 Salmonella per gram to start, this reduces the Salmonella to 1 organism per 1,000 grams of food. Greater Ds are used in other circumstances where standards are for log reduction are higher. 6.5D is standard for most intact roasts, 7D for poultry items, 12D for canned items.

Take a look at the chart below.

Each time/temp relationship is equivalent. In other words, the same level of pasteurization occurs on a food items cooked to 130 and held there for 112 minutes, or cooked to 150 and held there for 1.12 minutes, or cooked to 165 and held there for 2.13 seconds. While this isn't practical for a cooking on a grill, say, it might be if one is cooking in an oven where specific lower temps can be maintained. This is often done in restaurants that cook sous-vide or that cook using combi ovens, ovens that are designed for specific cook-and-hold situations. But one could, e.g., if one wanted a rarer burger, grill one to 140 internal then hold it in an oven that could maintain the requisite 140 for 8.6 minutes to get a 5D kill. (The temperatures and times listed in the table are also sufficient to also destroy E. coli O157:H7 in food (e.g., ground beef).) Regardless, the chart points out the dynamics of time @ temp.

For poultry (a 7D standard) the operative times are thus:

Temp Reached/Minimum Time for Chicken/Min Time for Turkey

140/ 35 Min / 33.7 Min

145/ 13 Min / 13.8 Min

150/ 4.2 Min/ 4.9 Min

155/ 54.4 Secs/ 1.3 Min

160/ 16.9 Secs/ 26.9 Secs

165/ <10 Secs/ <10 Secs

As you can see, for all practical purposes cooking to over 160 internal is not required for pasteurization. It can be required--especially in the case of poultry but also, for our purposes, in the case of barbecue, to cook to higher internals for quality purposes. Turkey thigh, e.g., isn't very palatable, imo, at 160, and brisket is barely chewable; both, however, would be safe to eat if they reached 160--that is if one could.

It should be clear that having an accurate thermometer is of utmost importance. Interior juices can be of any color and so can interior portions of the product being cooked. Young chickens frequently maintain red/pink color near the bones after cooking to safe internals; hamburgers might be grey thoughout even when raw or might maintain bright red coloring internally even after safe internals are reached, especially if other products were added to the meat before the burger was formed. Temperature is the only operative issue--not color.

Tip-sensitive thermistor or thermocouple thermometers are the best for checking internal temps (make sure they're accurate!). Non-electric, dial stem terms should NEVER be used for thinner items (imo, they shouldn't be used for checking internals of anything) as they can be wildly inaccurate. This is because they have a 1- to 2-inch-long bimetallic spring in the stem. The thermometer must be immersed in the food more than 3 inches, and the temperature reading is still only the average temperature across the bimetallic coil, or about 3 inches up the stem from the tip. This temperature measuring device is suitable for measuring the temperature of liquid products such as soup, where the temperature throughout the product varies only 1 degree, and items that are more than 3 inches thick--but to assure accuracy a tip-sensitive therm is best. Again, bimetal therms should NEVER be used for thin items like burgers and chicken breasts.

This is already a long post but I wanted to make another point I've made many times elsewhere, and one that is important to this thread as it is clear that the beans were being cooked one day for consumption the next, as many of us do as a matter of course when we cook ahead of time or cook more than we are going to consume immediately. The important point is the need for relatively rapid cooling after cooking for food items meant for storage for reheating/consuming in the future.

As discussed, pasteurization that occurs during cooking reduces the possible pathogens to a safe-to-consume level. Once the cooked item's temp falls to less than the top end of the danger zone (again, 130, and I am talking about any part of the product which, practically speaking, is usually the surface temp and not the interior as surfaces cool more quickly in most cases) then growth of any existing pathogens can occur (pathogens that might have survived pasteurization). The critical temp range--the range in which relatively rapid growth by the largest amount of different pathogens can be expected--is 85-115.

Once a food item's temp has moved into the danger zone the clock starts, growth occurs, and food must be consumed in a reasonable period of time so as not to pose a danger. This 'reasonable' time is what constitutes the '4-hour rule', meaning that food should be consumed within 4 hours of its temp moving to less than 130 (or above 40 in the case of cold foods that are warming up). The actual time is dependent on the temps and the time so, like above, it is really a time @ temp situation. Without going into further details on this at the moment, suffice to say that if food is not going to be consumed in less than 4 hours any part of the food items falls to less than 130 (or rises, in the case of cold foods, to more than 40), it should be cooled quickly then fridged or frozen.

Items like pork butt and brisket that are often rested for a prolonged period can be temped by placing a therm on or near the surface of the item before foiling and placing in a cooler for resting. After the rest, and provided the temp has not dropped to less than 130, the butt, say, can be removed from the foil and pulled while still hot. But the pulled pork should then be cooled quickly (NOT packed in bulk while still warm/hot as cooling will then take too long) by placing it shallowly in roasting pans, cooling further, then placing in the fridge to finish cooling before packing and storing. Alternatively, pull the pork, allow to cool by placing the pork in shallowly in a pan during pulling, then place smaller amounts in larger Zip-locs or FoodSaver bags. These bags can be sealed then place flat in the fridge or freeze (preferably with airspace under them) to finish cooling. The thickness of the pork should not be greater than 1 inch.

This appoach can work for soups, pots of beans or chili, and sauces as well. Alternatively, the entire pot of the item can be place in a sink of iced water (taking care that the water/ice level is lower than the rim of the pot, of course), and the pot stirred from time to time so that its contents cools evenly, and draining some water and replacing it with more ice, as needed.

Again, hot food items are in the danger zone when their temps drop below 130; cold items when their temps rise above 40. If the temps are maintained outside of the danger zone there are no safety issues and the food items can be held at correct temps for very long periods (though excessive periods often cause quality problems, there aren't safety issues). Safety concerns begin with the temps fall or rise into the danger zone and the concerns grow as time in the zone grows.

Though one sees food-borne illness (FBI) that occurs from undercooked foods (burgers, e.g.) or contaminated raw foods (the recent E. coli in spinach issue), by far one sees a greater occurrence of FBIs from foods that have been 'temperature abused' viz. foods that have been allowed to enter and remain in the danger zone for too long. This occurs most often during holidays (because of food cooked in advance and improperly cooled before being reheated, or from leftovers) and during the summer months when picnics/outdoor eating are commonplace (for the same reasons). If food is placed out on the holiday or picnic table without temp control (chafers for hot items, iced platters/bowls or some other method of maintaining cold) for cold items, the food should be consumed relatively quickly--in less than 4 hours, in most cases. Food not consumed in this period of time should be discarded--not saved. Though the length of time the food will remain safe varies according to time @ temp guidelines (some items might be safe for many more hours than 4, depending on the item, the specific temp that the item reached and the range of temps in the danger zone that occurred (was it a cold item that had an increase from 40 to 65 over 4 hours? a hot item that fell from 130 to 105 over 3 hours?), unless you know this information, temped the food while it sat on the table, watched the clock, etc., for practical purposes it is best to assume 4 hours maximum--and then pitch all food after that point. Storage and then consumption of food that has been in the danger zone for more than 4 hours is not recommended. Technically, again, depending on the variables noted above, the food might be safe for storage and later consumption, (I am not automatically assuming of FBIs from these foods would occur), at the very least I would not serve foods that have been in the danger zone for loonger than 4 hours, then stored, to children, the elderly, or those with compromised immune systems as these individuals are far more succeptible to FBIs.

Kevin

On edit: Edited trichina time/temp info and provided explanatory link